'This is the story of the most astonishing and destructive thing never to happen to London'

Mapping London’s unbuilt motorway network - story 144

Welcome to Bridged2050: creating an even better Barnes during this climate crisis

London very nearly remade itself around the car. Not in the casual, incremental way we know today, but through a vast, engineered web of elevated motorways slicing across neighbourhoods from Barnes to Bow. It sounds outlandish. It was very nearly real.

If you’re new to the story, the clearest primer sits at Pathetic Motorways. It explains how, in the 1960s and 1970s, planners drew up a masterplan for hundreds of miles of orbital and radial routes threading through the capital.

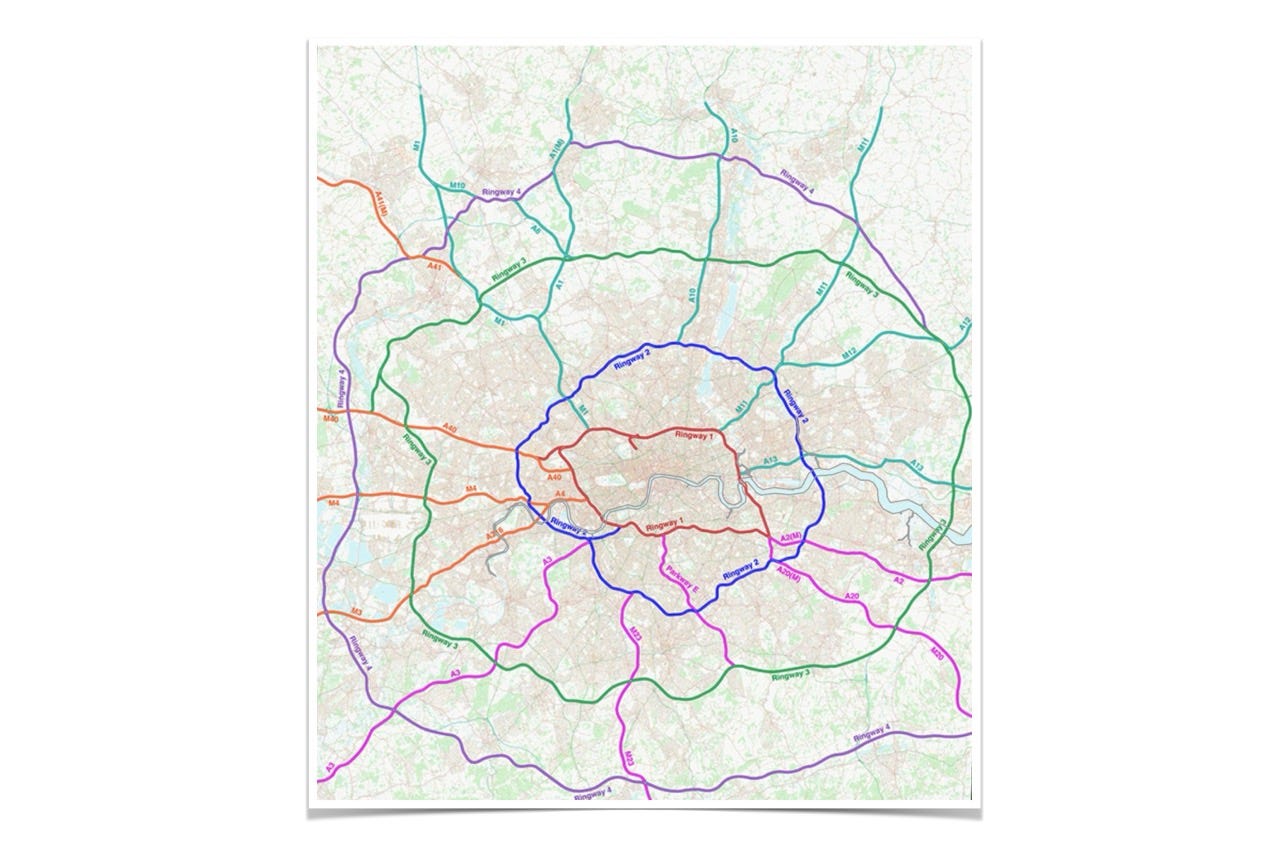

For the first time, the scale of these ambitions have been revealed. Chris Marshall has spent two decades piecing together

what he believes to be the first truly accurate map ever made of the abandoned plan to cover London with US-style motorways (London Centric)

Roads.org.uk, founded by Chris, worked with SABRE, the online archive of the Society of All British and Irish Road Enthusiasts, to create dynamic zoomable maps of the whole network.

As Roads.org.uk put. it,

No complete map of the Ringways has ever been made, including by the people who designed them.

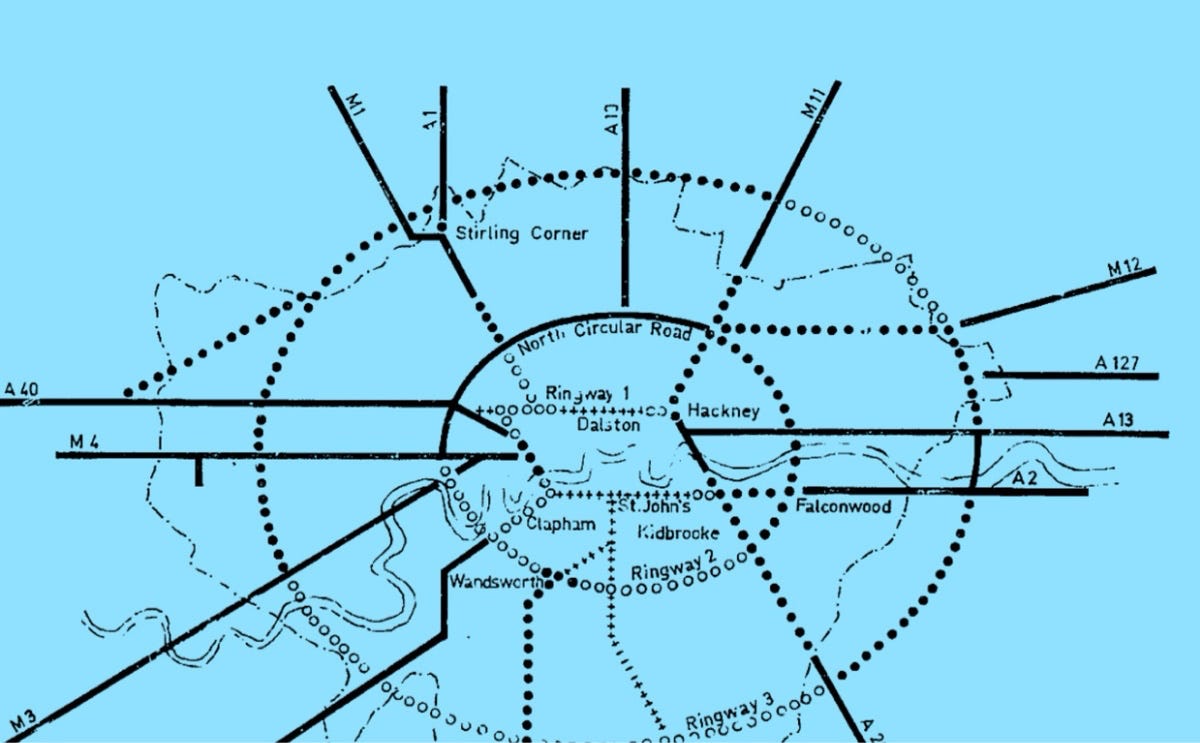

The planners, engineers and politicians who devised and promoted the Ringways back in the 1960s and early 1970s had an idea of the network they were creating, of course. They had high-level schematic maps of the pattern of roads they wanted to produce, but most were little more than thumbnail sketches.

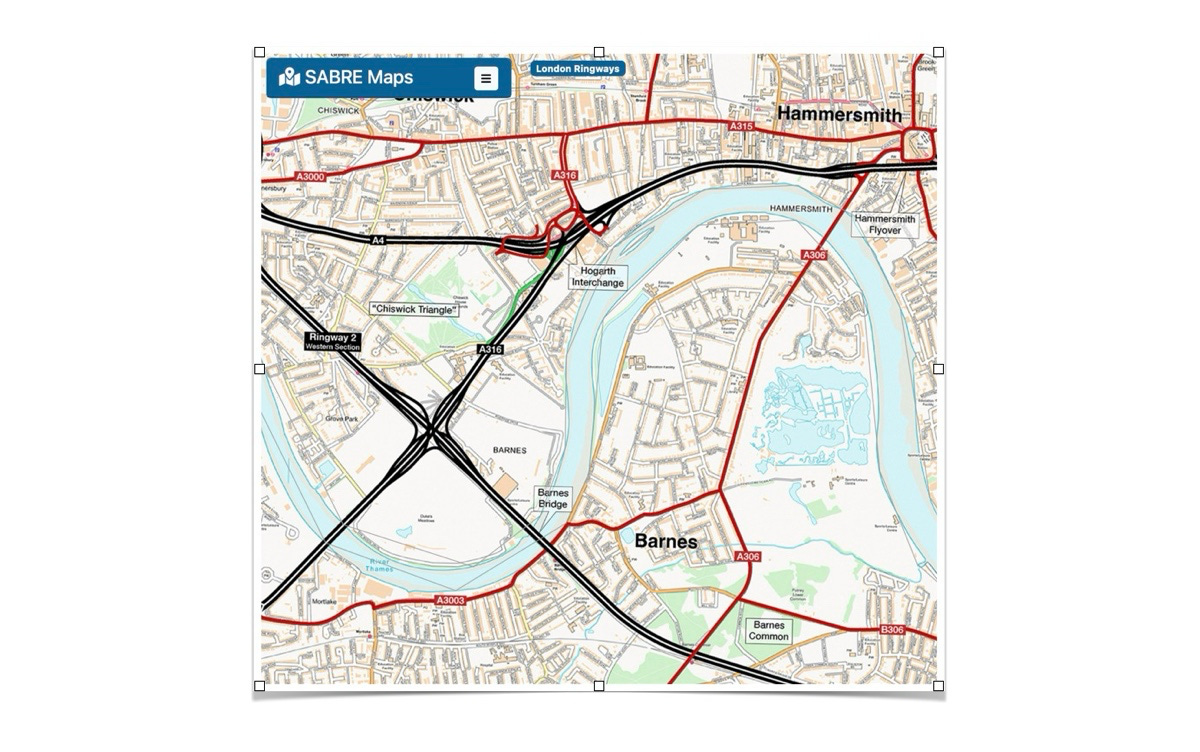

SABRE’s maps let you drill down. Here, for instance is a stretch of Ringway 2.

The maps reward exploration. Do take a look and, if you can, support SABRE. They guard an important piece of the country’s memory.

Notes & thoughts

The Ringways grew from a simple belief: the best way to cope with more cars was to build more roads.

America pursued that logic to the extreme. They chose to prioritise cars over people - ensuring ever larger roads (highways) in the hope of ensuring ever faster speeds, provisioning vast car ‘parking lots’ in city and town centres, kettling pedestrians and fining jaywalkers who resisted.

London flirted with the same idea as these maps show, but never went all-in.

Despite that, as London Centric reports.

There was cross-party political support and an academic consensus behind the plan — and even, initially, strong public support for road building as the solution to congestion.

“They all thought they were saving London, that there was a looming catastrophe and they could save the city,” says Chris Marshall, founder of the website roads.org.uk. “There was a lot of academic weight, political impetus, and a public sense that something had to be done about the traffic.

Of course that feeling didn’t go away. At the Barnes Fair this year, BCA shared a series of memory boards. One included the story of how Barnes residents woke up one morning to find … a plan to build a motorway through Barnes. That was in 1988.

Something does need to be done about traffic.

But the old reflex — build more and bigger roads — was wrong then and it’s wrong now. More roads induce more traffic.

The latest data from the Department for Transport and Transport for London (November 2025) shows the opposite is true here in south west London. The closure of Hammersmith Bridge has reduced traffic volumes on the surrounding river crossings.

So we’re left with a sharper question: what sort of place do we want to live in? How much traffic? And, as important, what kind of traffic?

Bridged2050 believes we need less traffic and a change the traffic mix. We need fewer private cars and a better mix of essential vehicles — emergency services, traders, buses and taxis — moving more freely, more safely, and with far less harm to the people who actually live here.

The Ringways belong to another London: a version of the city that never quite arrived. We need to remember that as we shape the one we still have.