All eyes on Parliament again

With a key government spending review imminent, the future of Hammersmith Bridge could finally be decided. Well, maybe - story 83

Hammersmith Bridge may be about to have a moment.

The cost of restoring the Bridge to allow cars, buses and commercial vehicles across is so high that only the UK government (UKG) can realistically fund it. Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, is set to announce the UK government’s spending plans for the next three years on 11 June. That is followed a week later by the Department of Transport issuing its strategic plan.

There’s a possibility that we’ll hear something—directly or indirectly—about Hammersmith Bridge.

Only a possibility.

The Hammersmith Bridge Task Force recently reconvened after a 18month hiatus. As far as anyone can tell, it has yet to complete its work on traffic data, preferred options, and costings—all minimum requirements if the Department for Transport (DfT) is to make a credible bid to the Treasury.

Whether the decision is taken next month or - please, no - next year, there are several options available to ministers.

Unsurprisingly, many come down to scale and structure of funding.

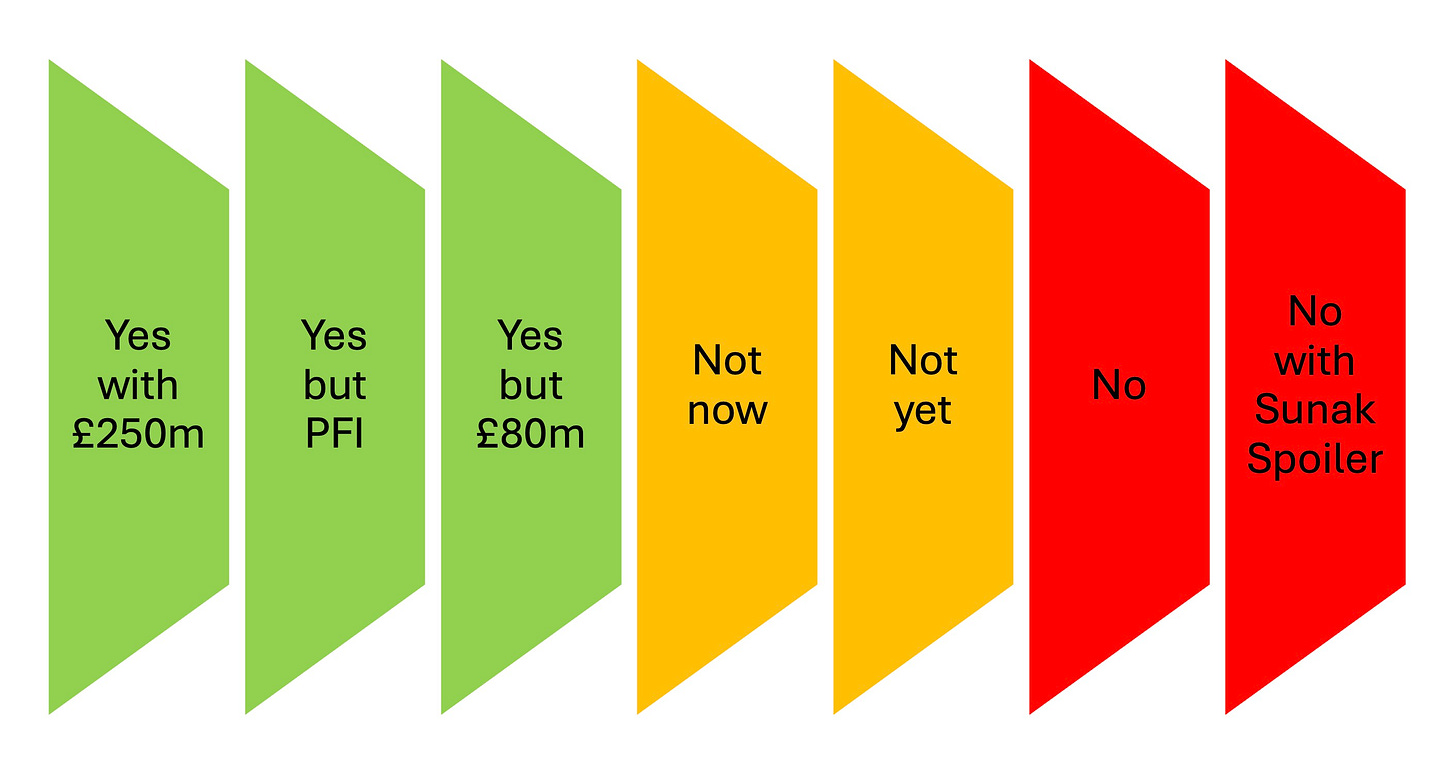

Yes definitely, maybe, perhaps, no, not ever

This is (nearly) a sliding scale of options from an unambiguous green light to a hostile refusal.

Yes here’s £250m

This figure comes from the most recent forecast cost for a full restoration of the Bridge. It’s already out of date, and costs will only rise over the three to five years it would take to complete the works. The Chancellor could simply allocate £250 million and instruct DfT and partners—the Mayor of London and Hammersmith & Fulham Council (which technically owns the bridge)—to cover any future overruns.

Yes but use PFI

The Chancellor has form when it comes to Thames crossings and private funding. She has already approved one Thames crossing using private finance, like the Private Finance Initiative (PFI)

Earlier this year, Heidi Alexander, the transport secretary, gave formal approval for the £9bn Lower Thames Crossing. Private capital for public projects never went away but seems to prominent again.

Silvertown Tunnel, the newest Thames crossing, was delivered under PFI. This approach has its advantages, as London Centric reported,

Part of the reason that the tunnel has been built while other TfL projects continue to linger on the drawing board is that it has been financed using private funds, with investors from around the world putting up the money in return for healthy returns over the next 25 years.

By contrast, public transport projects such as the Bakerloo line extension and Crossrail 2 are expected to rely on substantial funding from central government, which is harder to obtain

But there are trade-offs.

Take pricing.

Private investors expect returns. According to Transport Action Network, tolls on new crossings like the Lower Thames Crossing might need to rise to £8.10 for cars and £14 for lorries to cover costs.

And there’s the impact on nearby crossings. Introduce a toll at Hammersmith, and drivers may keep using Putney or Kew Bridge, which remain free—undermining both revenue and the policy goals of congestion management.

Yes here’s a third, £80m

Another option: partial funding. The Chancellor could offer £80 million as a down-payment, inviting TfL and Hammersmith & Fulham to make up the rest.

But H&F has already said it cannot afford a third-share contribution without introducing tolls.

Unless coupled with approval to use PFI as well, this would be frustrating for all parties. For supporters of the restoration, approval has been given but could not be delivered. For those opposed to restoration, the option remains alive,

Not now

This could be the quiet kill. No formal rejection, just a lack of urgency. A vague nod to ‘priorities elsewhere’, ‘fiscal constraints’, or ‘regional equity.’

In practice, ‘not now’ pushes the matter into the long grass—perhaps until a different Chancellor, a different transport secretary, or a different set of Treasury officials decides to pick it up again.

Not yet

A delay dressed up as prudence? The government could acknowledge the project’s importance while pointing to incomplete business cases, modelling gaps, or unresolved traffic displacement concerns.

Again, the Bridge remains in a kind of suspended animation—neither greenlit nor shelved. Within the machinery of Whitehall, ‘not yet’ can mean anything from next quarter to next Parliament.

No

Rarely stated in such terms, but always a possibility. If the Department for Transport hasn’t made a strong enough case, or if the Treasury decides the numbers don’t add up, outright refusal is an option.

No with a Sunak Spoiler

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak cancelled the northern leg of HS2, pledging to invest the saved £4 billion into local roads and rail instead. The Prime Minister also instructed officials to sell properties along the cancelled HS2 route. The decision was described as ‘salting the earth’, effectively preventing the project’s revival.

It is diffult to imagine how this would be possible with Hammersmith Bridge. But it has been done before so remains a precedent.

Notes & thoughts

Or maybe better described as requests to the Chancellor and her colleague, the transport minister.

Clarity on the process

Whatever the decision, make clear what has been decided, even if that is ‘nothing’.

It’s entirely plausible that the decision-making timeline for Hammersmith Bridge is operating on a different rhythm to the wider Spending Review. If so, let’s hear it plainly. A short public statement from the Hammersmith Bridge Task Force—‘we’re not ready yet’—would go a long way.

The silence, six years and counting, is no longer neutral. It erodes trust.

Clarity about the decision

When the time does come, explain the decision. Whatever the outcome, ministers owe the public not just a decision but the reasoning behind it.

Let’s say the government chooses not to restore the Bridge for vehicles. That is a valid decision if it’s made consciously, not by default. But it must be framed not as failure, but as a future. A bridge for walkers, cyclists, and wheelchair users is not a compromise. It is a statement.

But if ministers land on the this outcome for the wrong reasons—lack of money, electoral caution, strategic drift—then we risk paralysis. Boroughs may hesitate to invest in local improvements, unsure whether traffic will one day return. Businesses and planners will second-guess. The surrounding area will stall; preserved in uncertainty, a northern corner of the borough suspended in civic aspic.

A firm answer, whatever it is, lets the city adapt. Without it, everything waits. Forever.