What our cars say about us

Which drivers might be the most willing to switch to sustainable transport? - story 79

Since starting this blog, I’ve returned to one topic more than any other: cars. Their impact on our built environment is profound. If we want to imagine an even better Barnes and Mortlake, the most transformative step would be reducing private car use.

I am in good company. The Mayor of London has been pursing this goal since 2018, with mixed success. Richmond Council say they want this to happen but are taking a more subtle, incrementalist approach.

That’s why the decision about Hammersmith Bridge matters. The Chancellor’s Spending Review in June is the next possible date for a clear decision on the Bridge’s future. If cars are not to be restored, that affects many more than the 20,000 drivers who used to use that crossing.

Over the past year, I’ve spoken with car owners, occasionally in less-than-friendly circumstances—cycling along the Terrace toward the High Street roundabout is not for the faint-hearted. But I’ve also tried to understand the psychology of driving: what motivates it, what sustains it, and how we differ in our attitudes.

Three broad groups seem to emerge:

car-first

driver-first

people first

Three views on four wheels

Being car-first is not always about the vehicle itself. For many the car is a symbol of their freedom: the right to move unimpeded, as one might claim dominion over castle and surrounding grounds. This group resists restrictions, seeing them as assaults on personal liberty. In 2024, some of them became the so-called “Blade Runners,” vandalising traffic cameras during the ULEZ expansion. In my conversaion around SW13, I have noticed many in this group are also distrustful of climate policy. The country where this outlook thrives is America. It has dominated the design of their urban landsacape for over 100 years.

The driver-first mindset is more pragmatic. These are people who drive as a means to an end. These are parents doing the school run, workers commuting, people going shopping or visiting family. They are practical. Their use of the car is functional, not symbolic. In my conversations, many in this group support climate goals in principle but balk at any disruption to daily routines.

Then there are the people-first advocates. Like the car-first cohort, they are motivated but in the opposite direction. They believe cities should be designed for people, not vehicles. They emphasise fairness, public health, and sustainability. They ask: how do we build a shared environment for all, not just those who can afford to drive?

In short there are three groups which reflect their focus, taking the perspective of one, few and many:

Car-first – people who identify with the car as a symbol of their beliefs

Driver-first – people who prioritise practicality, flexibility, and everyday needs

People-first – advocates of public space and mobility systems centred on human experience

Why does this matter?

This blog is trying to answer one question:

How do I live my best life in the world’s greatest city during this climate emergency?

So many answers lie in personal change. I can achieve some things on my own. But many depend on collective choices and that means understanding the people we live alongside. On this most sensitive of topics, this segmentation provides one way of doing that.

I want to cut through the noise created by the car-first group. They are intense, vocal and occasionally right. The drama, the emotions make for compelling social media posts and occasional news bulletins. They are a minority and need to be heard. That fury makes it hard to assess the merit of their case, to find that occasional grain of useful challenge. The car-first group should not be allowed to frame any of these discussions. As important, I don’t want to use their tactics against them. I do not want to to demonise them. I am not going to bait them or shout them down.

When the time is right, later this year, I want to talk about the issues raised in this blog with fellow residents and others. One of the draft guidelines for this phase is designed to ensure I avoid meeting only like-minded people. I will include people I consider to be car-first.

I am much more interested in the driver-first community. They are the swing voters of the mobility debate. I will be talking with them.

In part this is because they form the majority. In part because I believe some in the driver-first group could be persuaded to switch to sustainable travel. And in part because I agree with their root demand - improve the choice, the cost, the fairness. I do not think this group should be allowed to decide what constitutes a minimum standard. Any one particular aspect of driving a car could be well-nigh impossible to replace with a like for like experience. The bus will not stop outside your block of flats. But the driver-first are right to expect the replacement service, in the round, to be as good in terms of convenience, speed, cost, safety and health impact.

How many are in which group?

There is no single poll that looks at who in London, let alone Barnes and Mortlake, fall in to which group. It is possible to construct a useful ‘rough and ready’ typology.

It seems that between 10–20% of Londoners express strongly held, values-based opposition to car-reduction measures. So car-first. Here are three post-Lockdown surveys that inform that estimation.

ULEZ Expansion (YouGov, July 2023)

London-wide support: 51%

Outer London opposition: 45% opposed, with ~25% strongly opposed

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (Transport & Environment, 2021)

London-wide support: 51%

Opposition: 27%, with 12–15% strongly opposed

British Social Attitudes Survey (DfT, 2021)

64% agree people should drive less for environmental reasons

But 25–30% of drivers resist road pricing, traffic restrictions or bus lanes

Other academic and institutional analysis points the same mix.

Institute for Government (2023)

Describes the anti-ULEZ/anti-LTN community as an "intense but minority-held" movement, more ideological than practical.

University of Westminster (Rachel Aldred et al.)

Vocal opposition to LTNs clustered in neighbourhoods with high car ownership and low active travel

IPPR / Climate Network

Estimates ~15% of public have a strong pro-car identity, linked to scepticism of government intervention

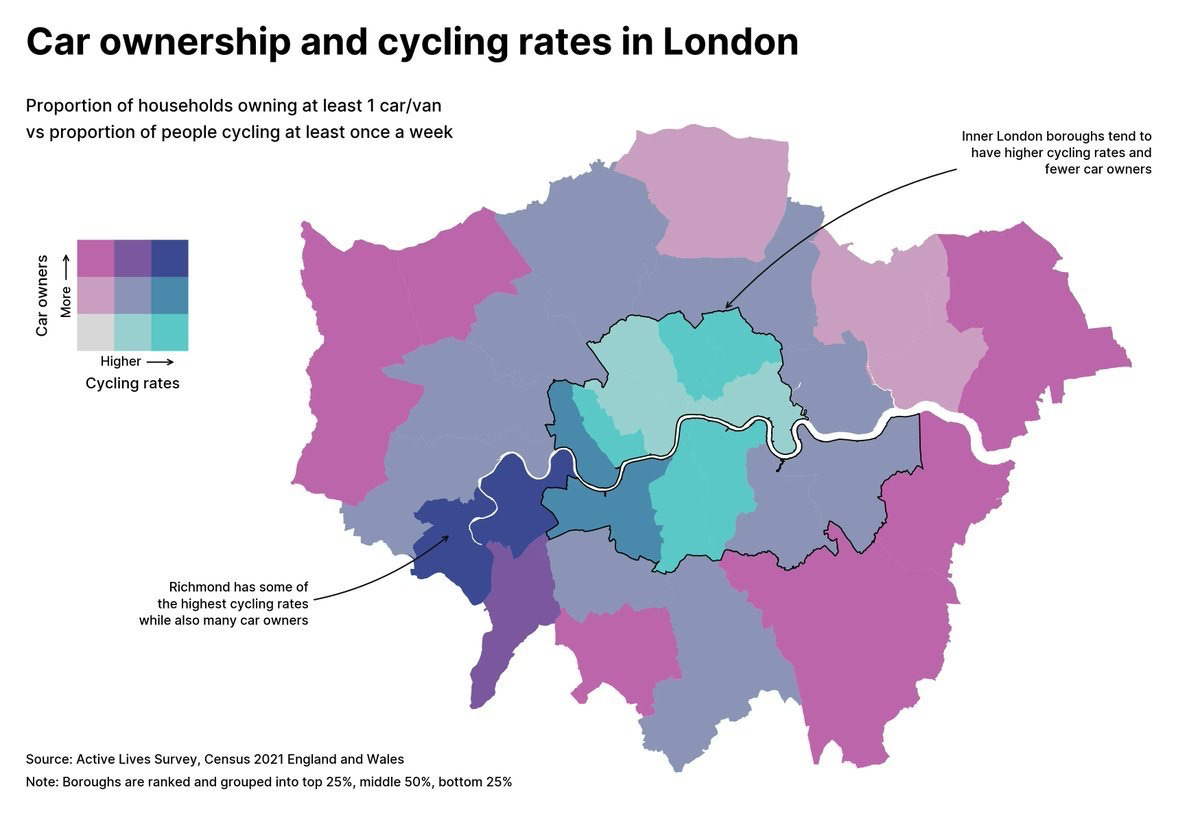

And yet, context matters. Car ownership in the inner boroughs (40-50%) is much lower than in the outer boroughs (70-80% with Richmond 75%). Infrastructure explains much of this. It is so much easier to walk, cycle or use public transport in the inner boroughs. The greater the car dependency in a borough, the larger this politically vocal minority of car-first community. Inner boroughs might comprise 10-20% car-first; outer boroughs might be 20-30%.

Richmond lies on the boundary of the groups. This is because of its relative wealth, the quality of its public transport in the northern and middle part of the borough and its proximity to the inner boroughs. This unusual mix is captured in the chart below. Only one borough straddles both banks of the Thames and only one borough has high car ownership rate and high cycling rates.

Maybe this is the profile of a borough in transition?

The same analyses shows the driver-first category is 60-70%. Two dynamics are worth mentioning.

I am now in the third group - people-first. That was not always the case. Until ten years ago, I was driver-first I drive from south west London to west London everyday. It was more convenient. I always drove to the supermarket for shopping. I changed. Lots of people are changing. Not enough but the direction of travel is clear. The transport profile of London is changing.

What is happening to younger Londoners?

I am going to do a longer story about this, so these are the headlines.

London’s twenty somethings are starting to exhibit a distinct transport profile. They have been raised on free public transport. They dominate shared bike rental use. They struggle to book a driving test. A flat to own is expensive, even shared. Buying a home is out of the question for many, unless ‘bank of mum and dad’ can step in. Many in the outer boroughs - including Richmond - live with familes which no longer have multiple cars. Could this be a generational change in transport use?

I am influenced by my professional experience in the media sector. Something happened in the first decade of this century to change a long-standing media consumption habit. Teenagers would fall out of love with the BBC but return to its tv and radio in their twenties. This seemed to be related to them securing their first job or home. Then social media launches followed by the streamers. By the time of the London Olympics it was clear there was a new media consumption habit at large. The great migration of twenty somethings back to the BBC was diminished.

Could the same thing be happening in transport in London including Barnes and Mortlake?

Notes and thoughts

Assume there are three broad categories of relationship with cars:

car-first – people who identify with the car as a symbol of their beliefs 20%

driver-first – people who prioritise practicality, flexibility, and everyday needs 65%

people-first advocates of public space and mobility systems centred on human experience 15%

I need to revisit these numbers in the light of new surveys.

Focus on the driver-first community. Their expectations are reasonable. They can be persuaded to make the move to sustainable travel.

More work is required on London’s under-35 community. Literally the next generation, their views are not yet hardened and they could be under-going a transformational change in lifestyle for that age-group, evidence for which we are starting to see in survey results.